I’m a Nurse Practitioner working in the belly of America’s nightmare: The Opioid Epidemic

In March 2017, I thought that I had finally landed the perfect career as a pain management nurse practitioner. In my mind, this was the perfect specialty because growing up and throughout college I had endured sports injuries; luckily, I never broke any bones or needed surgery. I spent a lot of hours in physical therapy. Ice, heat, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit, an occasional massage, and ibuprofen were my pain management treatments. Given my diverse life experiences in healthcare and my ability to establish rapport with anyone, I was motivated to help people manage their pain. I never anticipated becoming an insider to one of America’s nightmares: the opioid epidemic.

During my first few months, I spent each visit getting to know my patients in order to learn about the root causes of their pain. Moreover, I learned that many of them were dealing with mental health issues. As the months passed, I discovered that their pain was not improving, and in some instances, their pain was becoming worse. Many of the patients were taking high doses and quantities of methadone, fentanyl transdermals, morphine, oxycodone, and hydrocodone. And they were asking for more. For example, I once had a patient that had a history of lower back pain from several failed surgeries, and he needed a total right knee replacement. He had an Intrathecal Pain Pump (ITP) that supplied a steady dose of dilaudid directly to his spinal fluid and a prescription for oxycodone 20 mg, PO, q4h, PRN for breakthrough pain (#180). One day, this patient scheduled an emergency appointment because he had exacerbated his lower back pain while helping a friend move. He could barely stand upright, and he was requesting to have the rate of his ITP increased and additional oxycodone. In my heart, I felt that this patient was already prescribed too much medication; however, as a practitioner in my clinic, I’m required to collaborate with my supervisor, who’s an anesthesiologist, about changing patient treatment plans. After we reviewed the case, he decided to adjust the patient’s ITP and prescribed #100 additional oxycodone tablets for two weeks. Needless to say, I was appalled. The patient had already taken #180 tablets of dilaudid, and now he was receiving an additional #100 tablets. When the patient returned two weeks later for his follow-up, he was still in pain. He reported that he had consumed all #100 tablets of oxycodone and was requesting his regular monthly refill.

At this moment I realized that our pain management system was broken. Patients were being treated not to lessen their pain but to medicate it. They were receiving outrageous amounts of narcotics, a temporary fix but not a long-term solution. I saw this kind of treatment as doing more harm than good, for patients were walking a fine line between dependency and addiction. Although I was not the person writing the prescriptions, I felt like a professional drug dealer. At this time, healthcare providers were not regulated by the Federal government; instead, they followed their own judgment.

By October 2017, and after attending the annual Texas Pain Management Conference, my supervisor made me responsible for weaning patients off carisoprodol, a very addictive muscle relaxer. During the conference, he and I learned that the CDC had issued a new guideline: “Carisoprodol used in conjunction with narcotics increases the risk of addiction and death.” I repeated that statement so many times to the patients who were taking carisoprodol that I began to feel like a robot. Patients’ resistance was overwhelming. They wanted to be pain free and saw carisoprodol as their solution. They all argued that they weren’t the ones abusing their medications; they had been taking this medication for several years, and they never had any side effects. For the most part, they were telling the truth. They weren’t abusing their medications. Though I empathize with their arguments, this continued treatment was not the path to their wellness. So, despite their pleas, I spent months weaning every patient off carisoprodol and then several months finding an alternative muscle relaxer as an effective replacement.

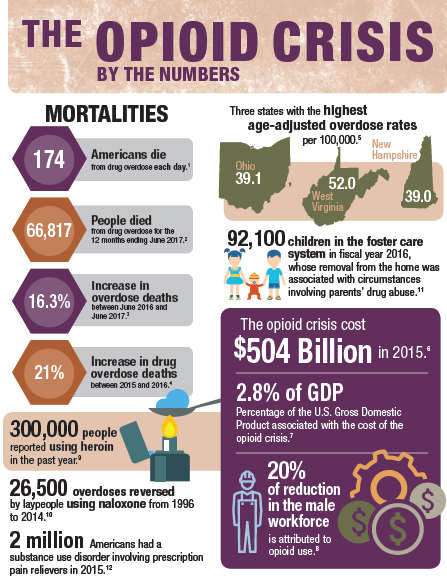

By the end of 2017, thousands of people in America had overdosed on narcotics and illegal street drugs. The 833 opioid-related deaths in West Virginia are always on my mind. Maybe it’s because I care and that I have a conscience. That’s a lot of people to die from one substance, not by war or a natural disaster. “It will never happen to me” is the response that I heard from all the patients that I weaned off opioids or decreased their dosages beginning in March 2018. During this time, the CDC issued a new guideline to combat the opioid epidemic. As a result, we had to wean every patient either off opioids or decrease their dosages to 90 Morphine Milliequivalents (MME) by January 2019. The experience of weaning patients off carisoprodol had prepared me for the ranting and intense discontentment. Being empathetic and allowing the patients to state their concerns were the keys to my success. Each month, I listened to patients complain about increased pain, severe insomnia, and withdrawal symptoms. Some patients passed away from other causes, and others turned to marijuana, methamphetamines, and cocaine to help manage their pain. These patients were discharged from the clinic for illegal substance abuse; however, steroid injections were offered to help manage their pain. To continue my efforts in weaning patients off or down on their medications, I cited several timely headlines that seemed to be happening almost daily. For example, I discussed the fentanyl-laced synthetic marijuana in Connecticut (https://www. npr.org/2018/08/16/639133355/dozens-overdose-in-connecticut-park-on-tainted-synthetic-marijuana). Eventually, we reached our goal and every patient’s narcotic intake was reduced to 90 MME per day by New Year’s Eve 2018.

Now in 2019, patients continue to complain about pain; they still ask for an increase in their pain medications, and they continue to seek out other methods to manage their pain including Spinal Cord Stimulators (SCS), Intrathecal Pain Pumps (ITP), CBD oil, and sometimes opting to have surgery again. Many of these techniques have resulted in low to moderate success in improving their pain.

I’m relieved that guidelines were set to help healthcare providers realize that the excessive opioid prescriptions were out of control. We were, in fact, doing more harm than good. The new regulations helped both the providers and patients realize that they needed to seek other alternatives for managing pain. Moreover, the CDC guidelines make it easier for providers to tell patients “no” when they request additional narcotics or an increase in their dosage. On the other hand, I do not agree with how the government forced physicians to decrease the strength of patient dosages to help combat the opioid abuse. A more effective method would have allowed providers to review and regulate patients’ cases individually. Not all pain is created equally. Some patients may not need to be prescribed narcotics, while others, who have had serious injuries and failed surgeries, do.

During my two years of working in pain management, I have come to realize that chronic pain can take a toll on people both mentally and physically. Chronic pain can disrupt personal relationships. Hence, I let my patients know that there are people in this world who still care and that they are not alone. There are other people who are enduring similar situations. I care for my patients, I teach them about the cause(s) of their pains, offer alternative medical treatment plans, listen to them, allow them to vent, and give them words of encouragement. Our society has a habit of placing stigmas on situations that they do not understand. Sometimes, I’m the only person that they may see and confide in on a monthly basis.

The purpose of my blog, IAMAprilPhillips.com, is to teach others about the most common pain conditions seen in clinical practices and to offer suggestions for standard care practice.

References

CDC. (2019). CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

CDC. (2019). Prevent Opioid Misuse. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/patients/prevent-misuse.html

National Institute of Health. (2019). West Virginia Opioid Summary. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/opioid-summaries-by-state/west-virginia-opioid-summary

Neuman, Scott. (2018). Dozens Overdose In Connecticut Park On Tainted Synthetic Marijuana. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2018/08/16/639133355/dozens-overdose-in- connecticut-park- on-tainted-synthetic-marijuana

Zacny, J. P., Paice, J. A., & Coalson, D. W. (2012). Subjective and psychomotor effects of carisoprodol in combination with oxycodone in healthy volunteers. Drug and alcohol dependence,120(1-3), 229–232. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.006